This was another class assignment for my grad certificate. I incorporated Michael Stipe in this by using him in photo examples. Because I love him.

Originally submitted for JOMC 712 at UNC on April 30, 2012.

Communicating with your Communicator

A guide to graphics, color and typography

It’s happened to all of us: you’ve asked your marketing pro to make a graphic for an upcoming event and you thought you were totally clear in what you wanted but what ends up in your inbox is not at all what you imagined. You know he or she can’t read your mind, but surely what you asked for was clear enough, right?

On the flip side, a seemingly simple project lands on your desk and it needs to be done yesterday. You get started, only to end up going back and forth with the client because the original instructions include a low-res graphic with a vague description. What should have taken a few hours turns into an all-day back and forth on graphic, color or word choices. Isn’t there a way this could have been solved from the get-go?

Regardless of which side you’re on (and some of us have been on both), it’s a frustrating situation to be in. Since none of us are mind readers (or at least, we can’t prove that we are yet!), there has to be a better way.

“By sharing a common fundamental understand of visual communication, my clients and I could progress more quickly towards achieving the communication goal at hand,” Jill Powell, Marketing Manager at the University of North Carolina says.

Heather Davis, Marketing & Communications Specialist at Johnson College agrees. “The more others understand my needs and the College’s needs and why they exist, the more smoothly I can manage my time and resources.”

Miscommunication may even cost you a chance at getting the promotional exposure you need.

“If someone sends me a press release that is a mess,” Patrice Wilding, lifestyles reporter for the Scranton Times-Tribune says, “I am not going to want to respond or work with them specifically since they have not demonstrated a basic understanding of their material or the professionalism it takes to communicate with a serious publication.”

So to make everyone’s already hectic careers a little less so, here are some important concepts to keep in mind when embarking on a new visual project.

Graphics

A picture is worth a thousand words, but you don’t need to remember that many.

“It seems just about every week I have conversations with clients about why their low resolution image pulled from a social media website will not suffice for a print piece, or why a tiny graphic they created in an office productivity application will not render nicely on a t-shirt screen print,” Powell says.

While you may not be a pro at Photoshop, you can be a pro at learning a few key photo and graphic ideas to help your communicator create the best possible outcome.

Resolution: refers to the quality of an image. Typically, you’ll hear “hi-res” or “low-res” images. Low-res images are usually anything you’ve saved from the web and are best avoided if possible. “It makes my job easier when I am sent pictures that are of a higher resolution,” Davis says. It’s better to err on the side of high resolution rather than low. High resolution photos can always be made into lower resolution, but the reverse is not true.

If you are asking your communicator to also act as photographer, it may be helpful to give him or her a bit of direction in the type of photo you’re looking for. One of Poynter’s self-guided course outlines three types of photos.

Informational: basically, a person, place or thing. Not extremely visually interesting but literally gets the information across.

Example:

Michael Stipe on a step and repeat. source

Passive: staged photos, with a posed person, place or thing, usually in the form of a portrait.

Example:

Michael Stipe photographed by Slava Mogutin for Whitewall Magazine. source

Active: real time, real life, not staged photos. These capture the action as it’s happening, and tend to make the most visually pleasing photos.

Example:

Michael Stipe live in Raleigh, NC. source

If you’ve already got the photos but don’t know which the best to choose are, JProf.com has a great article that can help you get started on narrowing it down.

Color

More than just ROYGBIV.

“There’s a reason why we use certain colors,” Davis says. And it’s not just because it looks pretty. Color theory is a complex subject, but a basic understanding of a few color concepts will help you communicate your ideas with your communicator immensely.

Color Wheel: You may remember learning about primary and secondary colors as a youngster in art class. This handy tool is extremely useful when creating color schemes for projects, and understanding how it works will give you the ability to give great direction.

Example of a color wheel

Warm colors: the colors on the wheel ranging from red to yellow. They give a feeling of urgency, energy, passion and excitement

Cool colors: the colors on the wheel ranging from blue to violet. They give a sense of calmness, relaxation and professionalism.

Neutral colors: black and white, as well as shades of gray, brown, beige and cream. They are especially effective when used as a backdrop for more vibrant colors.

Commentary colors: colors on opposite ends of the color wheel. They are often visually pleasing when used together.

Analogous colors: colors next to one another on the color wheel.

There are plenty of resources on the web to help you delve more into color and color theory, including the more involved subjects of hue, chroma, saturation, brightness, shade, tint, etc. For more information, check out Smashing Magazine’s three-part series (1, 2, 3).

If your client or company has a predetermined set of colors that it always uses, make that clear in your project instructions. If you’re working with a communicator who primarily works in one area, he or she will probably understand what you need even if you don’t know the specific color attributes. For example, if you’re dealing with someone who works at the University of North Carolina and your request includes the phrase “Tar Heel Blue,” he or she working on the project will likely know the exact hue, tint or shade for that.

Text and Typography

Read between the lines.

Take time and consideration when your piece has a text component. If you’re pitching a publication, make sure your press release highlights the most important items. “I like for the message and/or relevant information to be clear and easy to identify,” advises Wilding. “This makes my job easier when it comes to supporting the merits of the story and actually writing/coordinating the art for a story.”

Organizations like newspapers will already have a set typography. However, in other outlets you may have the opportunity to control the look and feel of your text. Understanding some simple typography will help you steer your communicator in the right direction.

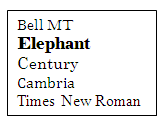

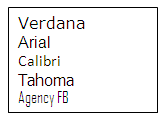

Serif: tiny strokes at the end of the letters

Sans Serif: literally, without those tiny strokes on at the end of the letters.

If you’re interested in getting more in-depth with typography, Poynter offers a free self-guided course. To help you in picking out typeface, read Smashing Magazine’s article on font familes.

Whether you’re the person who will be doing the actual piece or the client requesting the work, make it a point to remember these basic definitions when you’re about to embark on a new project. If you’re the person on the giving end, take a few extra minutes before shooting off that email or requesting that new project to make sure your direction is clear and that you’ve hit all the important points (making sure to include pertinent graphics in the correct resolution, color suggestions and any copy). If you’re on the receiving end, take a few seconds before getting started to make sure you understand what the client wants and to make sure you have all the necessary tools and direction. “Teamwork, patience and flexibility are important in visual communications,” says Davis. I’d add communication and knowledge to that list as well.